Commander-in-Speech: State of the Unions from Washington to Biden.

President Biden’s State of the Union (SotU) address on March 7th – the last of his current term, and possibly his last ever if current polling proves prophetic – has been called “fiery”1, even “aggressive”2, while some suggested it was more akin to a campaign speech than a ‘typical’ SotU3. The latter not entirely unwarranted given Biden’s less-than-subtle swipe at his “predecessor” – a word he used no less than 13 times (and incidentally a record number for any president).

The SotU is considered one of the President’s most important speeches and should, on balance, remark on contemporary themes. In this note, using every SotU since the first by Washington on January 8, 1790, we investigate how and if the themes dominating the SotU changed, and calculate, using Natural Language Processing (NLP), the general sentiment of each address. We also explore whether the overall sentiment of the SotU has any sensitivity to the macroeconomic environment preceding it. To do this, we collected every address, including Biden’s most recent, from ‘The American Presidency Project’ hosted at UC Santa Barbara4.

Presidents’ speeches are mostly about…

…the economy. But with a caveat.

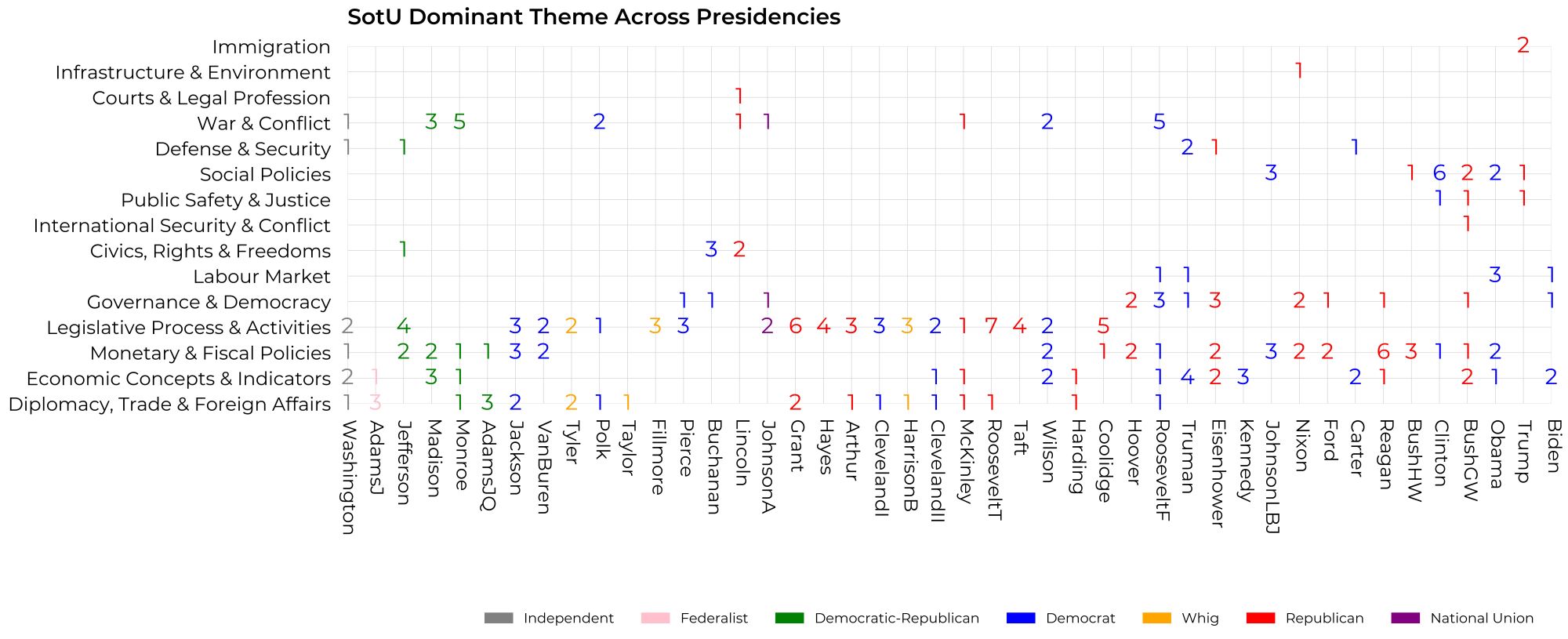

The below shows how many times a theme dominated a president’s speech. The values are colour-coded based on the president’s party affiliation5. A comprehensive description of the theme detection approach used here goes beyond the scope of the note, but it suffices to know that we leveraged a hierarchical taxonomy of ~ 600 key words and compounded phrases and counted their frequency within each address (the frequency is normalised to the total word count of each speech – essential as the speeches, both spoken and written6, have vastly different lengths). This approach allows for a desirable level of flexibility and is suitable for handling bloviated language used by politicians, especially for the carefully curated SotU.

At and right after the founding of the Republic, Presidents focused mostly on constitutional and legislative matters – expected given the context of administering a newly found democracy. However, following the Presidency of Warren Harding (1921-23), a period after which the US enjoyed rapid growth, some deregulation, and increased technological innovation and adoption, presidents started to focus more on the economy (Economic Concepts and Monetary and Fiscal Policy), as well as Domestic Policies, specifically Social Policies7.

There are a few notable ‘outliers’: Trump who was the first to talk plenty about Immigration (back-to-back in his 2017 and 2018 speeches); both Lincoln and Buchanan who delivered speeches dominated by Civics, Rights & Freedoms (mostly related to slavery); International Security & Conflict featured heavily in one of George W. Bush’s speeches (his 2002 address after 9/11); Nixon, in 19738, delivered both in writing and summarised in his speech, lengthy documents of which one was exclusively about Environmental issues; and no less than five of FDR’s speeches were dominated by War and Conflict, this, of course, during WWII.

Biden’s most recent speech was dominated by Governance & Democracy, a theme which includes concepts such as the Executive, organs of the federal government, and democratic freedoms. He used the word “democracy” / “democratic” a total of 14 times, and the word “freedom” no less than 15 times. While foreign relations also featured, the typical economic and social policies that presidents have tended to focus on in the recent past was, proportionally, only lightly addressed.

The sentiment of the SotU is…

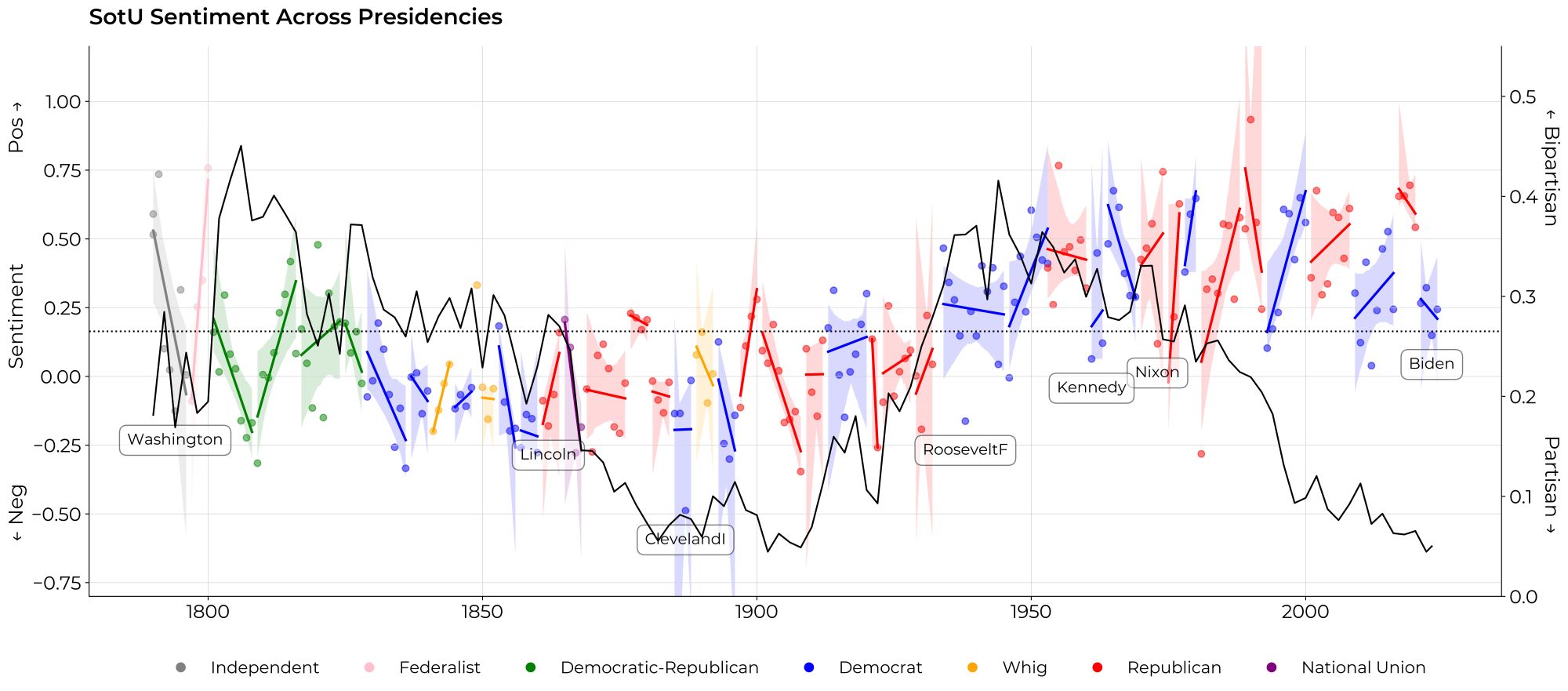

…highly dependent on the period, and, interestingly, on partisanship in the Houses of Congress. Again, a lengthy description of the Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools and library used to measure the sentiment is beyond the scope of this note, but we provide a brief technical description in the endnotes9.

Overall sentiment trended lower after the war of 1812, continuing this trend until the outbreak of the US Civil War in 1861. Hovering at that level, and below the long-term average, it picked up during FDR’s presidency (especially around the end of WW2) and peaked with H.W Bush in 1990. Since then, the trend has again been lower, barring the speeches of President Trump.

We also overlay, from earlier work, our Congressional ‘ideological overlap’ measure – a proxy of partisanship or polarisation in the Houses of Congress10. For most of the Republic’s history, more positive (negative) levels of sentiment in the SotU ran concurrently with greater levels of bipartisanship (partisanship) in the Houses of Congress (albeit with a spread in this relationship opening post-Nixon).

We hardly think this is coincidental. An elevated level of partisanship typically results in legislative stalemates, with presidents more inclined to use their address to amplify a lack of progress or articulate the challenges facing the nation more starkly. Being such an important speech, the administration’s speechwriters are also likely to use the opportunity to emphasizes an “Us vs. Them” impasse, portraying the state of affairs more negatively (than it might be) while criticising the political opposition more harshly. Moreover, in a highly gridlocked chamber, a president may tailor a fearmongering tone that might resonate with their base and draw attention to the opposition’s failures. Although this logic seems to have reversed over the past few decades!

Sentiment takes a (minor) cue from the underlying macro environment….

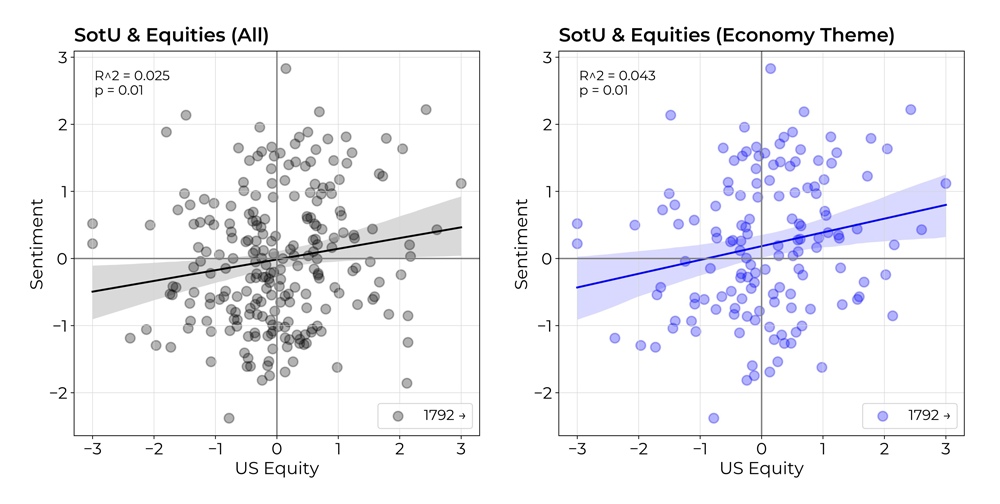

…which a priori and intuitively seems logical. Especially given that most SotU focus on the economy and domestic policy. In the plots below, we show the relationship of sentiment with the US equity market – for all speeches as well limited to only those speeches dominated by the Economy theme.

We calculated the annualised returns of the US stock market in the period preceding a speech (i.e., between the last and current speech), and find sentiment to be slightly more positive (negative) when the annualised equity returns the year preceding the speech were comparably higher (lower). When limited to speeches dominated by economics, the relationship is slightly more significant. We additionally tested for unemployment and inflation using the average percentage level and average YoY percentage changes between the last and current speech respectively. For inflation there seems to be a goldilocks effect, with both too high, and too low levels of average inflation in the year preceding the speech dragging on sentiment. While for unemployment, only extreme levels of high unemployment had a relationship with lower levels of sentiment11.

Is the Union in a state?

The SotU reflects the nation’s focus depending on the era’s demands. Notwithstanding, the SotU has mostly remained true to being a summary of domestic affairs, rarely dominated by say foreign relations. Measuring sentiment, especially on speeches which are filled with doublespeak, is susceptible to errors, yet here, nevertheless, accurately mimics issues of the time such as war, economics, and political partisanship.

1Reuters, March 8, 2024

2The Washington Post, March 7, 2024

3Chatham House, March 8, 2024

4The American Presidency Project is a rich resource of presidential americana. Readers are encouraged to browse their website.

5Eagle-eyed readers will notice the absence of James Garfield and William H. Harrison – the only two presidents that never gave any addresses, neither spoken nor written.

6The SotU has not always been in person. Before 1913, all messages were in written form, bar those of Washington and Adams which were all delivered as a speech. The first televised SotU was by President Truman in 1947, and in 1965 was moved to prime time.

7Social policies, in our taxonomy, include key terms associated with housing, social security, welfare, health care, and education.

8Nixon’s SotU in 1973 was a series of six written messages (both summarised in his in-person address and repeated as separate radio addresses). We treated these six documents as one, considered in its totality. We similarly treated the addresses of President Taft in 1911 and 1912, submitted in 4 and 3 parts respectively for those years, as one.

9For the sentiment analysis we leveraged Hugging Face’s “Transformers” library, specifically using a model called “DistilBERT”. The “Transformers” library offers highly sophisticated, pre-trained AI models capable of understanding context, nuance, and the complexity of human language. DistilBERT is a lighter version of “BERT,” a well-known language model, but faster and more efficient while retaining a high level of accuracy.

10Readers are welcome to download our paper “Partisanship in the US Congress since 1789. Has the US reached peak political fragmentation?” in which we proposed our ideological overlap measure. The paper is available on our website. In this note we used the average of the ideological overlap measures of the House and Senate.

11For comparable metrics between all variables (including sentiment), we remove their respective long-term averages, normalised by their individual standard deviation, and clip at 3 standard deviations to remove any outliers.

Disclaimer

ANY DESCRIPTION OR INFORMATION INVOLVING MODELS, INVESTMENT PROCESSES OR ALLOCATIONS IS PROVIDED FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY AND DOES NOT CONSTITUTE INVESTMENT ADVICE NOR AN OFFER OR SOLLICITATION TO SUBSCRIBE FOR ANY SECURITY OR INTEREST. ANY STATEMENTS REGARDING CORRELATIONS OR MODES OR OTHER SIMILAR BEHAVIORS CONSTITUTE ONLY SUBJECTIVE VIEWS, ARE BASED UPON REASONABLE EXPECTATIONS OR BELIEFS, AND SHOULD NOT BE RELIED ON. ALL STATEMENTS HEREIN ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE DUE TO A VARIETY OF FACTORS INCLUDING FLUCTUATING MARKET CONDITIONS AND INVOLVE INHERENT RISKS AND UNCERTAINTIES BOTH GENERIC AND SPECIFIC, MANY OF WHICH CANNOT BE PREDICTED OR QUANTIFIED AND ARE BEYOND CFM’S CONTROL. FUTURE EVIDENCE AND ACTUAL RESULTS OR PERFORMANCE COULD DIFFER MATERIALLY FROM THE INFORMATION SET FORTH IN, CONTEMPLATED BY OR UNDERLYING THE STATEMENTS HEREIN. CFM ACCEPTS NO LIABILITY FOR ANY INACCURATE, INCOMPLETE OR OMITTED INFORMATION OF ANY KIND OR ANY LOSSES CAUSED BY USING THIS INFORMATION. CFM DOES NOT GIVE ANY REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY AS TO THE RELIABILITY OR ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS DOCUMENT.