Penny wise, data foolish: funding cuts and revision errors at the BLS

In August 2025 the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) published one of the largest Non-Farm Payrolls (NFP) revisions on record1, drawing the accuracy of employment data into question. Some read it as a turning point for the US labor market; others saw it as a warning about data reliability just when accuracy matters most. In the post‑Covid cycle, it has not been the unemployment rate that flags a slowdown so much as a deceleration in hiring. This makes a clean measurement of hiring flows critical, but error strewn first prints can obscure turning points.

Any one NFP day sees the release of three numbers: a first estimate of the previous month’s payrolls, a revision to the number of the month prior to that and a further and (somewhat) final revision to the payrolls of the month two months earlier. Each revision represents a less and less timely convergence towards a more and more precise knowledge of the job market, the final number being the closest to the “truth”. Markets care about timeliness. Past information is priced in long before complete data becomes available, so subsequent releases and revisions tend to refine the narrative rather than overturn it, which begs the question: Do markets react to revisions?

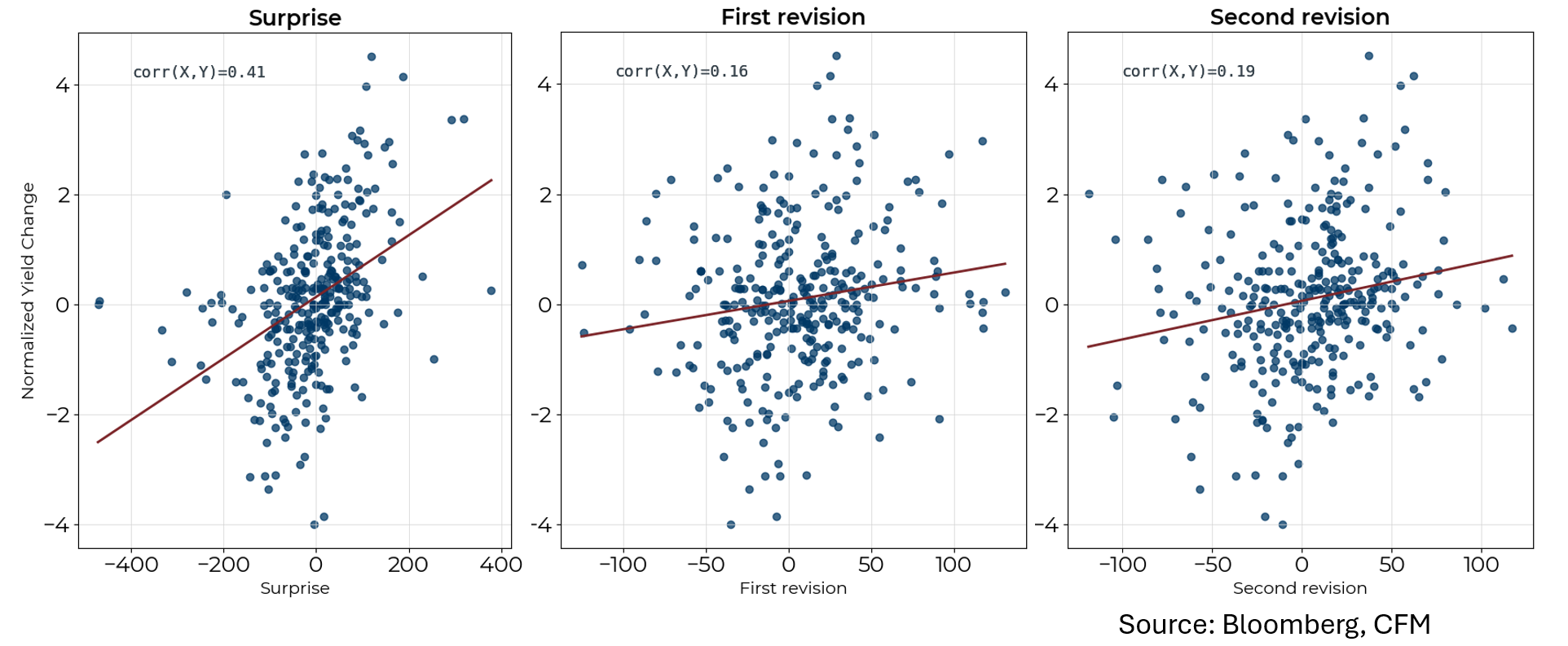

To test this, we inspect the normalized close-to-close change in the U.S. 2-year Treasury yield, known for its sensitivity to employment data given its close connection to changes in monetary policy, against the new arrival of the three figures delivered in each new jobs report. Because expectations are set ahead of the release, we define the “surprise” as the difference between the first print and the economists’ consensus, which updates up until the publication on the first Friday of the month. The equivalent surprise in the first revision is defined as its difference with respect to the previous month’s estimate while the second revision surprise is similarly the difference between the final estimate and the previous month’s revision. Our estimates (Figure 1) show that two‑year yields are most sensitive to the surprise, with a smaller response to subsequent revisions. The relationship between the first revision and the return is comparable to that of the second revision.

Revisions, by design, tidy up the record. They reflect late reports from employers and seasonal adjustments. Aside from the annual benchmark, the second revision is effectively the final number. If early releases have lost precision, it will show up in what they fail to explain. Having shown which vintage best explains market moves on release day, we now ask whether the latest revision noise is truly unusual in historical terms. To measure the magnitude of the measurement error of each release number, we compute the 12‑month rolling average absolute difference between that estimate and the final print (as close to the truth as we can get). This, in statistical parlance, is the Mean Absolute Deviation2 (MAD) of each estimate as it converges slowly to the most precise final print.

Figure 2 shows that the economists’ estimate is furthest from the final revision, while each subsequent BLS estimate and revision slowly converges to the final number. Revision error has stepped higher since 2024, led by the gap between the first and third estimates. More importantly, the 12‑month trailing MAD of revisions has surged for the second‑to‑third vintage, returning to Global Financial Crisis (GFC) territory. This means, there is increasingly more information embedded in the final report that is not captured by the flash estimate or the first revision. The first revision typically trims the error relative to the initial estimate, but the gap between “what we know now” and “what we learn two months later” has widened. For markets that trade on expectations, this widening gap is a signal in its own right.

The Federal Reserve does not, of course, pay attention to short term changes in employment conditions but rather takes a long term view. As already noted, the biggest market reaction to changes in NFP comes from the surprise in the first release relative to a consensus of economists’ forecasts and, as such, the market is assuming that the accuracy of the first NFP print remains a reliable indicator of what is to come. This assumption seems under threat, which prompts the question: should the market still react as the reliability of this initial estimate comes into question?

The BLS Budget helps explain part, though not all, of the deterioration in early‑vintage accuracy. Figure 3 shows that inflation-adjusted funding has been squeezed post-Covid, which forces trade‑offs such as slower sample recovery and delayed methodological upgrades. A rather limited squeeze didn’t bite as much in 2012–2020, when a more stable economy kept revisions contained. However, the post‑pandemic churn made measurement harder and the budget constraint compounded it. Under today’s funding path the direction is adverse: the budget in real terms (purchasing power) continues to erode and further cuts are expected. Under Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” proposal, an 8% budget cut is slated for 2026. That means smaller or slower‑to‑recover samples, thinner follow‑up to non‑respondents, postponed methodological changes, and longer intervals between sample redesigns and seasonal re‑estimation. The damage lands where it matters most, the first print, so more of the truth arrives later as late reports are processed and adjustments catch up. Budget is not the whole story, but it amplifies the noise. If appropriations keep falling in real terms, wider and stickier gaps between initial and final estimates and a heavier reliance on revisions to read the labor market might be inevitable.

The market reacts to payrolls precisely because it is seen as an indicator of the future path of Fed moves. However, the Fed also tends to tread carefully when data becomes noisier. Chair Powell has signalled greater reliance on alternative gauges of labour demand, the Beige Book among them, at the September 2024 and July 2025 meetings. The growing importance of the final release of NFP could delay rate decisions in the coming meetings. If the noise persists, the Committee may even defer additional cuts, especially with inflation risks skewed to the upside. For markets, that argues for placing greater weight on the final estimate and treating the initial print and first revision as provisional to avoid overpositioning on distorted early signals.

E.J. Antoni, President Trump’s initial pick to lead the BLS following the firing of Erika McEntarfer, expressed the view, earlier this year, that monthly jobs reports should be suspended, relying only on the quarterly data. The underfunding of the BLS may well be part of a broader strategy of economic opacity. This all plays into the hands of those with better, more timely and informed indicators of the state of the job market at their fingertips. Markets will surely become less efficient and less reactive to mainstream data that market participants take with a pinch of salt. Official statistics are public goods. Erosion of trust does not just add noise; it can fragment anchors. If distrust of national statistics spreads, will markets migrate to alternative job-postings data or private payrolls? If different communities switch to different datasets, coordination weakens, risk premia rise, and capital allocation could suffer. A world that leans more on private, proprietary data can widen information inequality. The philosophical question is not only “is the data reliable?” but “who gets to see what, when, and on what terms?”

1 The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for May was revised down by 125,000, from 144,000 to 19,000, and the change for June was revised down by 133,000, from 147,000 to 14,000.

2 Mean absolute deviation (MAD) is a robust spread measure, the mean of the absolute distances from the historical mean, that captures typical variation while being much less sensitive to outliers than standard deviation.

Disclaimer:

Any statements regarding market events, future events or other similar statements constitute only subjective views, are based upon expectations or beliefs, involve inherent risks and uncertainties and should therefore not be relied on. Future evidence and actual results could differ materially from those set forth, contemplated by or underlying these statements. In light of these risks and uncertainties, there can be no assurance that these statements are or will prove to be accurate or complete in any way. All opinions and estimates included in this document constitute judgments of CFM as at the date of this document and are subject to change without notice. CFM accepts no liability for any inaccurate, incomplete or omitted information of any kind or any losses caused by using this information. CFM does not give any representation or warranty as to the reliability or accuracy of the information contained herein. The information provided is general information only and does not constitute investment or other advice. This content does not constitute an offer or solicitation to subscribe for any security or interest.